No one here gets out alive.

Jim Morrison, The Doors

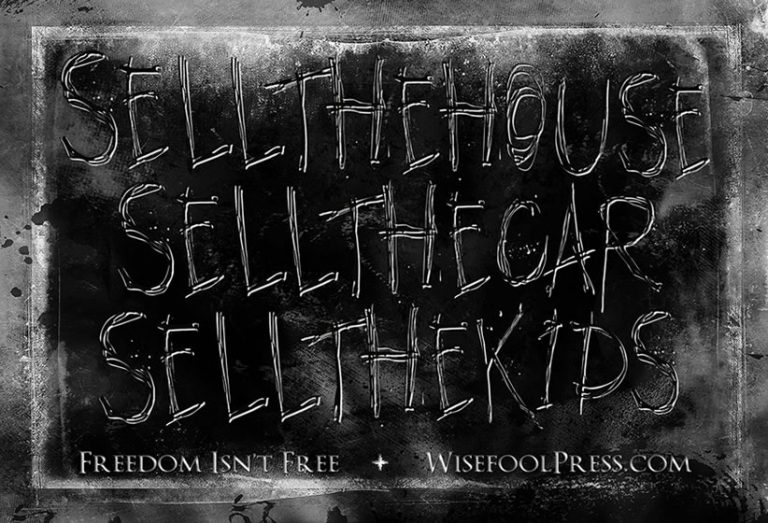

In the dreamstate, the only true act of madness is thinking. You can do it, but it’s strongly discouraged. Thought is what elevated Adam and Eve from common livestock to self-aware beings. They didn’t eat the fruit of the Tree of Being a Dumbass, they ate the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. Knowledge is arrived at by thinking, which, in the dreamstate, is the one true sin – original sin. In our version of the story, the anti-apple agent is played by Maya, who wants us to stay half-asleep in the sewer-dungeon, and the pro-apple agent is played by the Little Bastard Within, who wants us to wake up and live our lives. Which you call God and which you call Satan depends on which way you want to go.

Log In or Register to Continue

This is the end, Beautiful friend

This is the end, My only friend, the end

Of our elaborate plans, the end

Of everything that stands, the end

No safety or surprise, the end

I'll never look into your eyes, againJim Morrison

Jim Morrison (1943–1971) was an American singer, songwriter, and poet, best known as the charismatic and controversial frontman of The Doors, one of the most influential rock bands of the 1960s. Morrison quickly became famous for his deep, hypnotic voice, poetic lyrics, and wild stage presence. Beyond music, Morrison saw himself as a poet and published two volumes of poetry during his lifetime. His rebellious spirit and self-destructive tendencies made him both a countercultural icon and a figure of controversy. Today, he’s remembered not just as a rock star, but as a symbol of freedom, rebellion, and the darker side of fame.